Regional Economic Communities (RECs) in Africa are between countries in a specific sub-region. They aim to facilitate regional economic integration. The most powerful RECs encompass several countries covering a wide and contiguous geographic area. That’s because the countries involved usually share similar economic aspirations, history and culture.

In 2019, 15 regional integration arrangements with overlapping memberships of various countries existed. While they are formally independent, the RECs have an established relationship with the African Union (AU).

Existing trade agreements across Africa in 2019

Source: Adapted from Economic Integration in Africa in Abrego et al. (2020)

Examples of Regional Economic Communities (RECs)

The AU recognises the following eight RECs:

- Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS)

Also known as CEDEAO in French and established in 1975, ECOWAS has 15 member countries with a total population of over 397 million people. The member countries are Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Cote d’ Ivoire, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Senegal and Togo. ECOWAS has two sub-regional blocs called the West African Economic and Monetary Union (UEMOA in French) and the West African Monetary Zone, which comprises the English-speaking countries within the trade agreement.

- East African Community (EAC)

The EAC is a trade agreement of six countries in the great lakes region of Eastern African. Member countries include Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi, Rwanda and South Sudan. It was first established in 1967, dissolved in 1977 and revived in 2000. The EAC has a population of about 177 million people (1999).

- Southern African Development Community (SADC)

The current trade and cooperation agreement was adopted in 1992, but SADC’s origins date back to the1980s. SADC comprises 16 member states, namely, South Africa, Angola, Botswana, Comoros, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Eswatini, Lesotho, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Tanzania, Namibia, Seychelles, Zambia and Zimbabwe. SADC has a population of 345 million people.

- Arab Maghreb Union (AMU)

AMU unites five countries of North Africa and was established in 1989. The Member States – Morocco, Algeria, Libya, Tunisia and Mauritania – have an estimated population of over 102 million in 2020.

- Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA)

COMESA, which currently has 21 Member States, is huge and stretches from North Africa to Southern Africa to create a market with 583 million people. It was formed in 1994 and has an expanded free trade zone covering the EAC and SADC. Members countries include Burundi, Comoros, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Kenya, Libya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mauritius, Rwanda, Seychelles, Somalia, Sudan, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

- Economic Community of Central African States (ECCAS)

Consisting of 11 French, Portuguese and Spanish speaking Member Countries, the ECCAS kicked off in 1985 but was inactive for many years. It aspires to integrate Central Africa. Member States include Angola, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Republic of the Congo, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, São Tomé and Príncipe and Rwanda. ECCAS has a population of about 121 million people.

- Community of Sahel-Saharan States (CEN-SAD)

CEN-SAD has 29 Member States and all of them are signatories of other RECs across Africa. It was created in 1998. CEN-SAD hopes to create a free trade area in a geographical area that’s overlapping with the envisioned customs unions of other more integrated RECs such as ECOWAS and COMESA. CEN-SAD has a total population of over 658 million people.

- Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD)

The eight-member countries of IGAD are in the Horn of Africa (Eritrea, Somalia, Ethiopia, Djibouti), Nile Valley (Sudan, South Sudan) and Great Lakes ( Kenya and Uganda). IGAD was established in 1996 and sprung from the Intergovernmental Authority on Drought and Development (IGADD), which focused on the environment and development. 70% of the IGAD region sees very little rainfall, while youth comprise half of the 230 million people covered.

The AfCFTA and the existing RECs: Where do they fit?

First, the existing RECs will remain in place and become the building blocks upon which the AfCFTA will be constructed. The same goes for the existing customs unions such as the Southern African Customs Union (SACU) and others that might still be in the pipeline.

Second, it’s not clear how all the existing agreements will be integrated under the AfCFTA. What we do know is that the AfCFTA has a long-term vision of integrating all the RECs into a Single Africa Free Trade Area. As the AfCFTA becomes more established, more policy alignment and simplification of rules across the different RECs will be needed. Meanwhile, trade unions need to note the complexities and view RECs as another opportunity to assert their influence and develop demands.

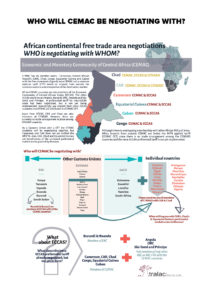

Who will negotiate with whom?

Experts use the complicated term “overlapping parallelism” when referring to how the AfCFTA is foreseen to exist in parallel with the existing regional trade agreements. The term is apt and describes an incredibly complicated issue. The overlapping parallelism between the AfCFTA and the RECs is particularly complex concerning who’s negotiating with whom. The main issue is that the 15 RECs have trade agreements and customs unions.

Always remember the following two things:

First, in a Free Trade Area (FTA), each member can negotiate tariffs individually with countries outside of the agreement and establish different rates. Country A, for example, can negotiate a 20% tariff on maize with China while Country B negotiates 5%.

Second, within a customs union, negotiations must be done as a single entity representing all members. Should the AfCFTA establish a Continental Customs Union, it’ll mean that where Country A and Country B could negotiate their own rates with China previously, they will then be bound to the rate negotiated under the AfCFTA customs union.

Trade unions must seek to do three things if they are to develop appropriate strategies and responses for the AfCFTA:

- Understand the complexities of the AfCFTA

- Maintain global solidarity through existing networks such as the International Trade Union Confederation

- Build knowledge networks at the national level. Labour research organisations, civil society organisations, NGOs and academic institutions are but a few examples of stakeholders that can help in establishing a solid knowledge of the AfCFTA.

The Trade Law Centre (TRALAC) has done valuable work on the AfCFTA and we recommend you visit their website for further reading on the AfCFTA and matters related to African trade and integration. We’ve reproduced some of TRALAC’s infographics to help unpack the complexities of who is negotiating with whom in the AfCFTA agreement.

Trading with countries outside of Africa under the AfCFTA

Remember that overlapping parallelism in RECs has implications for trading with countries outside of Africa:

“Is there now an opportunity to speak with a collective voice when engaging the European Union (EU), the United States (US), the United Kingdom (UK) and other partners such as China, India, and Japan? They are all prominent players in Africa and have plans for increasing and consolidating their presence on the continent. It will not, however, be easy to develop joint strategies on how to do so. Kenya’s decisions to start negotiations with the US on a bilateral trade deal and to conclude its own post-Brexit agreement with the UK have met with considerable opposition. There is an application pending in the East African Community (EAC) Court of Justice to review the Kenyan decision on a bilateral trade deal with the US. The argument is that intra African integration and the rules of the EAC (which purports to be a Customs Union) will be undermined.”

Gerhard Erasmus, Founder of TRALAC

You might like:

Marie Daniel

Marie Daniel is an Associate at Labour Research Service. Marie has an urban studies and development economics background and one of her research passions is organisation and participation approaches within the informal sector. She is intrigued by the manner in which participatory democracy is approached and implemented in South Africa.