With 1.2 billion people located within its geographical boundaries, the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is the largest free trade area by countries participating. Trade under the agreement began on 1 January 2021.

The AfCFTA is a game-changer for Africa. It could shore up Africa’s paltry contribution to international trade by lowering trade costs and increasing participation in global supply chains. The AfCFTA will reduce tariffs, address non-tariff barriers and create a free single market for goods and services. Beyond trade, it’ll see to investment, intellectual property, competition and the movement of people.

The Covid-19 health crisis highlighted many challenges in countries globally. Greater trade and cooperation is required to build back and forge ahead. With its projections of economic growth, the AfCFTA could help turn the tide in Africa. What can we hope to see when the agreement is implemented fully? Here are some positive and negative impacts of the AfCFTA.

The Predicted Positive Impact

1. The AfCFTA will lead to economic growth and the creation of jobs

The estimated income gains related to the AfCFTA could be as high as 5%. Some US$60 billion could be added to export values. According to the World Bank, the impact will vary in the different countries. Intra-Africa trade could increase by up to 12% to the value of $8.7 billion.

2. The AfCFTA can reduce poverty

Nearly every second person in sub-Saharan Africa lives below the poverty line. The World Bank Group notes that the AfCFTA can lift 30 million people from extreme poverty and 68 million more from moderate poverty.

3. Reduced trade costs will lower import prices and increase the purchasing power of consumers

Lowered trade costs will reduce import prices and increase the ability of people to buy a broad range of products. Through the AfCFTA, Africa will become a more attractive export market for companies.

Trade liberalisation can stimulate economies by increasing consumption and economic diversity. Some sectors would benefit more than others, for example, manufacturing and services. Developing the manufacturing sector will directly spur more job opportunities, while the growth of the services sector will occur in almost all countries.

Also expected through the AfCFTA are improved regional supply chains and more complex and valuable goods and services. Deepening the continental value chains could fast-track the industrialisation process, according to Trade Law Center (TRALAC). Smaller businesses particularly would have more opportunities in better continental value chains. It’s within the industrialisation process and value chain development that the AfCFTA promises to decrease unemployment in Africa.

4. Intra-Africa trade could increase by 8%-12% to the value of up to $8.7 billion

Free trade agreements don’t always result in improved trade. At the least, the AfCFTA can change the incentives to further improve inter-African trade. But more is required to improve trade than just eliminating tariffs. Africa would need, among other things, better customs administration, trade facilitation and domestic governance.

5. The AfCFTA could massively decrease the cost of trading

Of all the opportunities in the AfCFTA, better trade facilitation has the most impact, but only if it’s done correctly. A TRALAC study calculated that if the time for trucks to deliver goods in Africa decreased by just 20%, this would increase intra-African trade by a greater percentage increase than fully liberalising all intra-African trade. The improved efficiency would of course affect the existing non-tariff barriers such as border crossings.

6. The AfCFTA could facilitate the transfer of expertise and technology from global companies

The AfCFTA will increase trade, wealth and employment. But there is a reason for caution. Workers, women and communities could be harmed if the agreement is not implemented correctly.

The Predicted Negative Impacts

1. Positive projections are not guaranteed

The positive projections for the AfCFTA are not guaranteed. Some economists have disputed the claims that opening economies leads to growth. Trade agreements, argues Martin Myant of the European Trade Union Institute, are based on studies that show very modest benefits. Myant opines that the success of the AfCFTA will largely depend on countries having the necessary infrastructure and services. We support the view that, in the absence of national interventions and willingness, the AfCFTA will not succeed.

2. Unfair competition: SMEs can’t compete with large companies

“Trade liberalisation could jeopardise the most vulnerable through unfair competition.”

Companies have the opportunity to access more markets under the AfCFTA. But it also means increased competition, which could put small companies at a disadvantage. One argument for competition in trade liberalisation discourse is that it can stimulate innovation. Still, we must take into account the unique composition of Africa’s economy.

The informal economy employs about 86% of Africa’s workforce, compared to 69% in Asia and 40% in the Americas. These businesses face big headwinds and stand to lose much under the agreement if their issues remain, and especially the issues for women in the sector. Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) typically lack most of the things associated with having a competitive edge, such as enough capital and technological innovations. Some SMEs, including small producers and agro-manufacturers, will need sector-orientated protection to compete fairly with commercial and global firms.

3. Jobs, workers’ protection, social security and union rights could be hampered

Achieving the decent work agenda – Quality above quantity is not assured within trade liberalisation

With a more integrated African market, the AfCFTA will need to contend with dumping. Dumping occurs when a foreign company lowers the sales price of its exports to get an upper hand and ultimately destroy the competition. It undermines domestic production, job creation and economic transformation. Simply put, dumping could affect the ability of a country to achieve the Decent Work Agenda.

DEFINITION

Decent work – involves opportunities for work that is productive and delivers a fair income, security in the workplace and social protection for families, better prospects for personal development and social integration, freedom for people to express their concerns, organise and participate in the decisions that affect their lives and equality of opportunity and treatment for all women and men.

~International Labour Organisation

4. Workers will need assistance to instantaneously transition to a new sector

The possible negative implications of trade interventions on jobs are succinctly explained thus;

“Trade theory often assumes that those who lose their jobs from new trading patterns will instantaneously transition to a new sector, but this assumption has limited real-world validity. This is especially true of small-scale operators who lack transferable skills, and who may have other obligations that do not allow for mobility and transition and as such may not be able to find alternative employment. The effects of trade on employment vary at the country level, depending on factors such as asset distribution, on the type of trade (bilateral, multilateral or regional) as well as on the sector and skill-set of workers.”

~ United Nations Economic Commissions for Africa / Friedrich Ebert Stiftung

5. Increased demand for flexible workforces and decreased quality of jobs

Trade liberalisation depends heavily on a flexible formal workforce. But workers can become exposed to poor working conditions and little protection. It’s important to not only look at the number of jobs created or lost but also qualitative indicators such as pay, conditions of employment and employment security.

6. Higher female employment but not decent jobs

The case study below illustrates the impact of the process of trade liberalisation on small-scale farmers, workers and women in Kenya. Due to commercialisation, small-scale fruit and vegetable growers lost their incomes. Precarious work became widespread and the workers, many of them women, lacked proper occupational health and safety.

CASE STUDY

The commercialisation of farming in Kenya and the negative consequences for small scale farmers, workers and women

As export market opportunities opened up for Kenya’s fruit and vegetable sub-sector in the 1990s, small-scale production was displaced by large-scale farms and small-scale farmers who were unable to supply this market lost their incomes. Commercial farming provided employment for landless women, and processing plants, particularly in urban areas, employed young single women. However, commercial farming has increased risks to workers’ health as a result of pesticide handling and application. Whilst commercialisation of vegetable and fruit production can provide new employment, it often produces only casual employment in the food and transport sectors. These jobs are unlikely to have pension, material, annual leave or sickness benefits.

High dependence on processing plant employment is subject to the high seasonality of these jobs. These jobs also provide little to no opportunity for skills development and upward job mobility. These gender-differentiated outcomes are inconsistent with African States’ obligations to ensure that they do not discriminate against women.

~ Source: The Continental Free Trade Area (CFTA) in Africa – A Human Rights Perspective

7. Successful Free Trade Areas (FTAs) are supported by national policy and physical environment: Is this the case for the AfCFTA?

Multilateral institutions lack the same gusto emphasising the importance of national interventions in implementing FTAs as they do the positive impacts. With regards to employment opportunities in the AfCFTA, the World Bank predictions are over-optimistic:

“Implementation of AfCFTA would increase employment opportunities and wages for unskilled workers and help to close the gender wage gap. The continent would see a net increase in the proportion of workers in energy-intensive manufacturing. Agricultural employment would increase in 60% of countries, and wages for unskilled labour would grow faster where there is an expansion in agricultural employment. By 2035, wages for unskilled labour would be 10.3% higher than the baseline; the increase for skilled workers would be 9.8%. Wages would grow slightly faster for women than for men as output expands in key female labour-intensive industries. By 2035, wages for women would increase 10.5% with respect to the baseline, compared with 9.9% for men.”

Besides the spotlight on the quality of these jobs as illustrated by the case study on Kenya, there’s a catch to the Bank’s impressive estimations. Countries would need to adopt various interventions to achieve job creation. The interventions include “…facilitating a smooth and inclusive transition by supporting flexible labour markets, improving connectivity within countries, and maintaining sound macro-economic policies and a business environment that is friendly to domestic and foreign investors.”

But not many countries can afford the suggested interventions for achieving job creation. Also, we know from experience that policies that are friendly to domestic and foreign investors often come at a very high cost to the most vulnerable members of society. Within the AfCFTA, retaining programmes are touted as an intervention for minimising job losses. Trade unions should assess the feasibility of the interventions in their countries and formulate demands accordingly.

8. Increased power to large global multinational companies

It’s proven that trade liberalisation affects unionisation and the bargaining power of employees. Trade agreements can lead to large multinational companies increasing their power and ability to influence labour policy-making to their benefit.

Further areas of concern

There are many other sticking points to look out for in the AfCFTA, for instance, the unequal development of economies. Poor, small and landlocked countries stand to benefit less from the agreement and several have applied for differential treatment in the implementation of the provisions on the elimination of import duties and other tariffs. This is one example of how the AfCFTA negotiations and implementation can vary between countries.

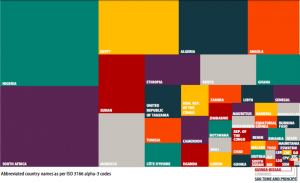

The relative size of African economies in 2017

Source: UNSD 2019, available at unstats.un.org

The outcomes of the AfCFTA processes will have a direct impact on the revenues of countries and their ability to invest in the required infrastructure, educational and social programmes.

You might like:

Labour provisions in free trade agreements – The trade union argument for inclusion

Also read:

Marie Daniel

Marie Daniel is an Associate at Labour Research Service. Marie has an urban studies and development economics background and one of her research passions is organisation and participation approaches within the informal sector. She is intrigued by the manner in which participatory democracy is approached and implemented in South Africa.